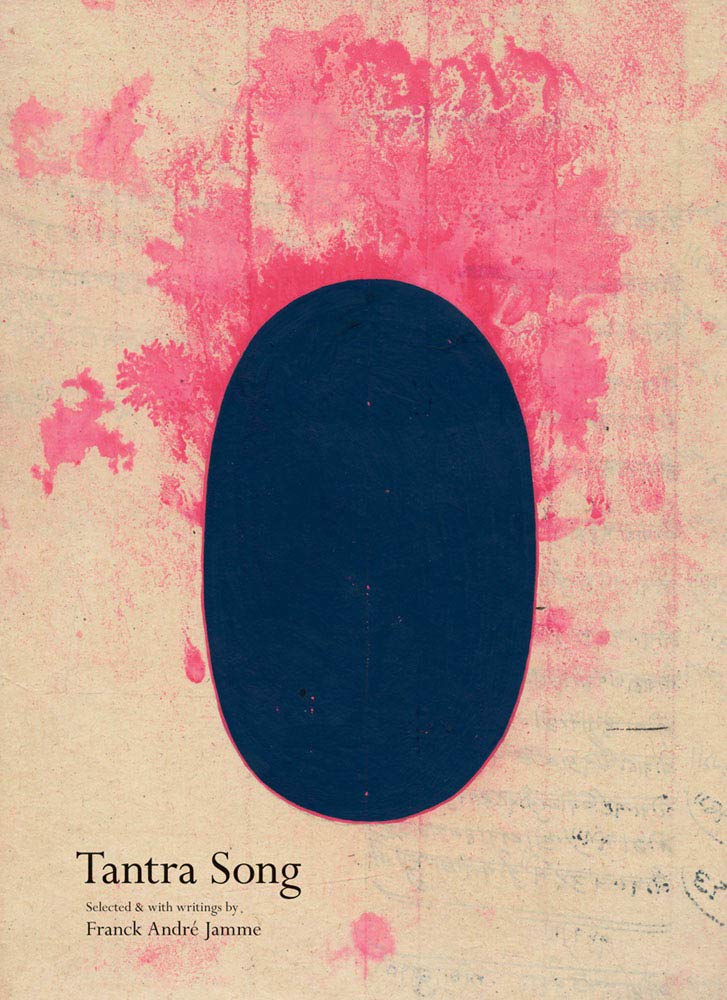

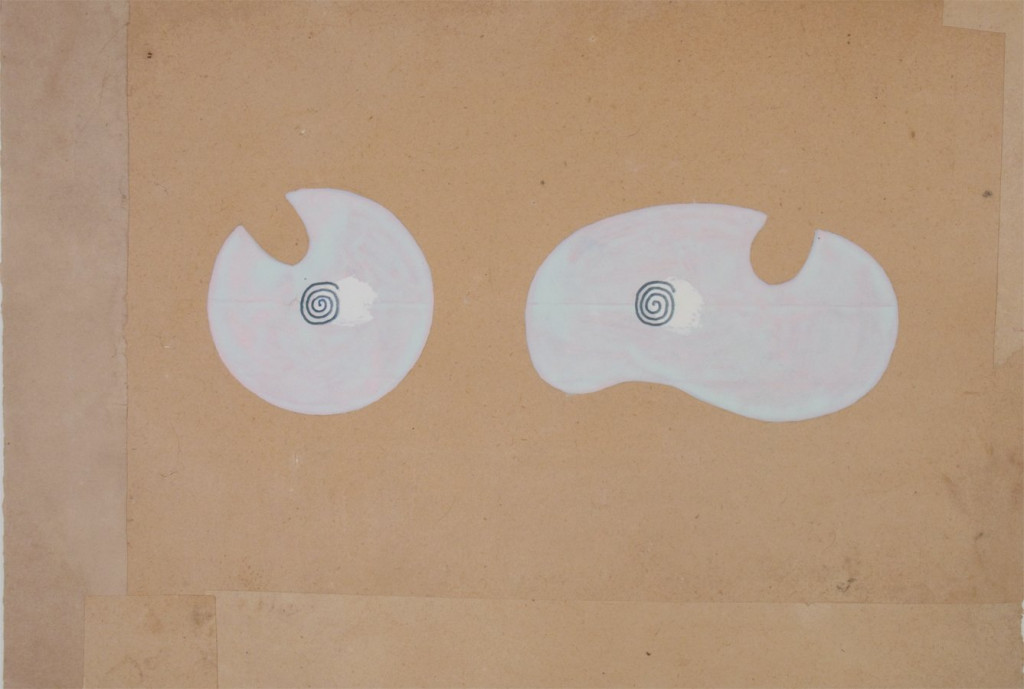

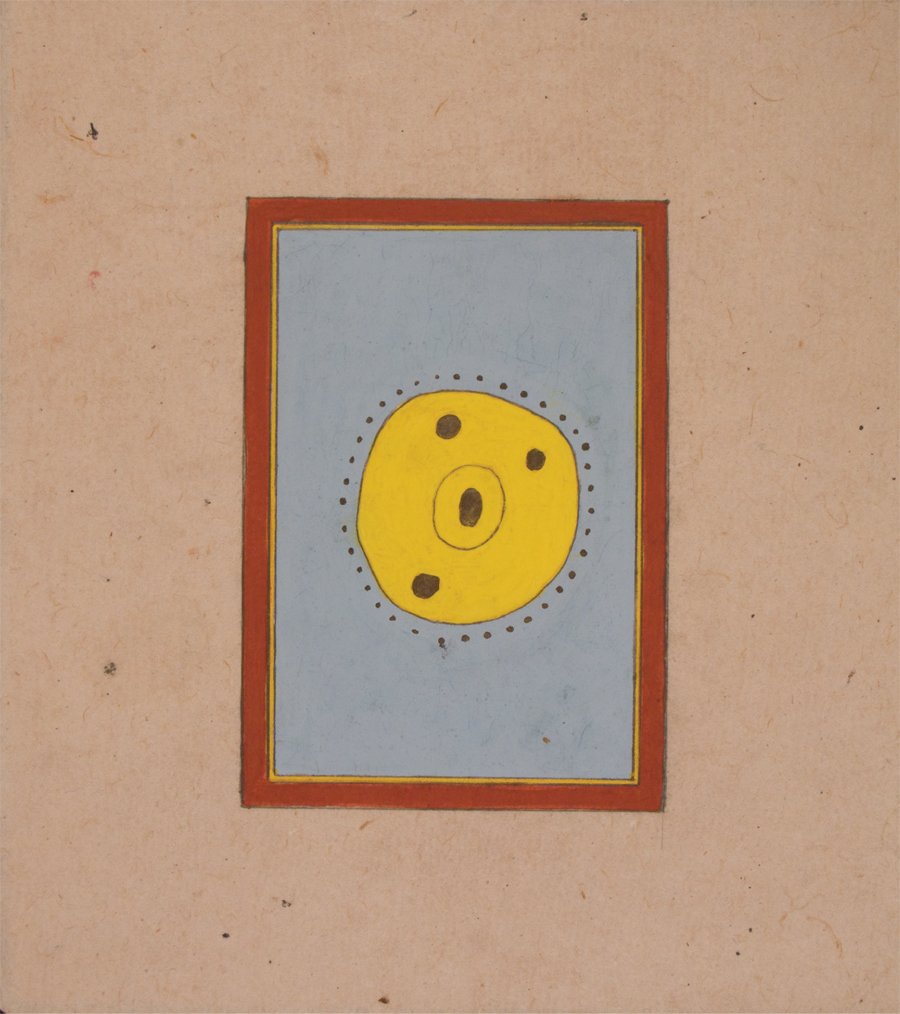

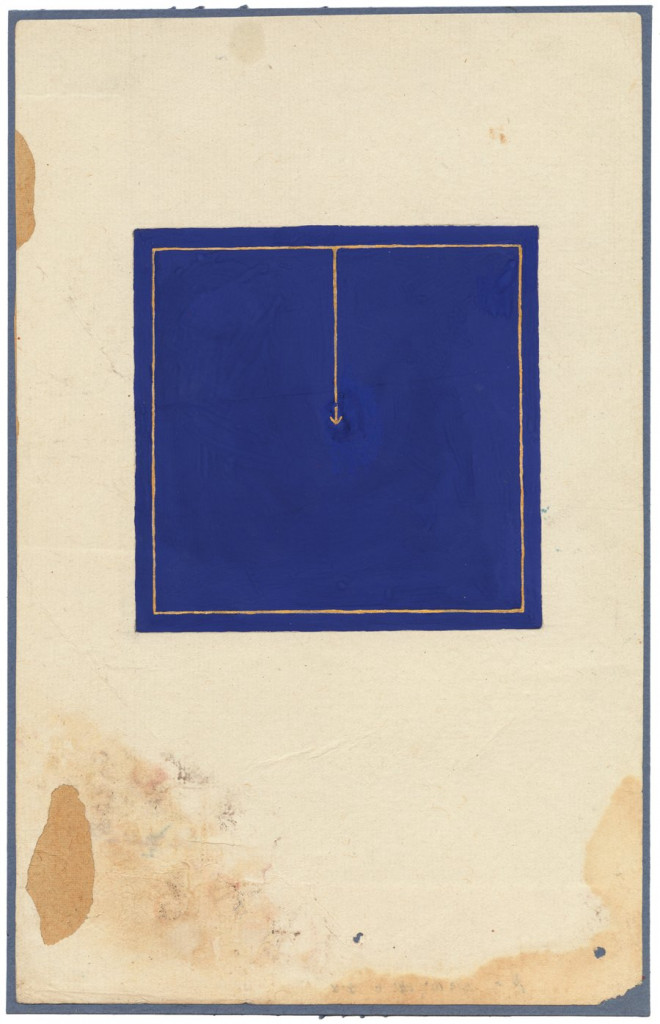

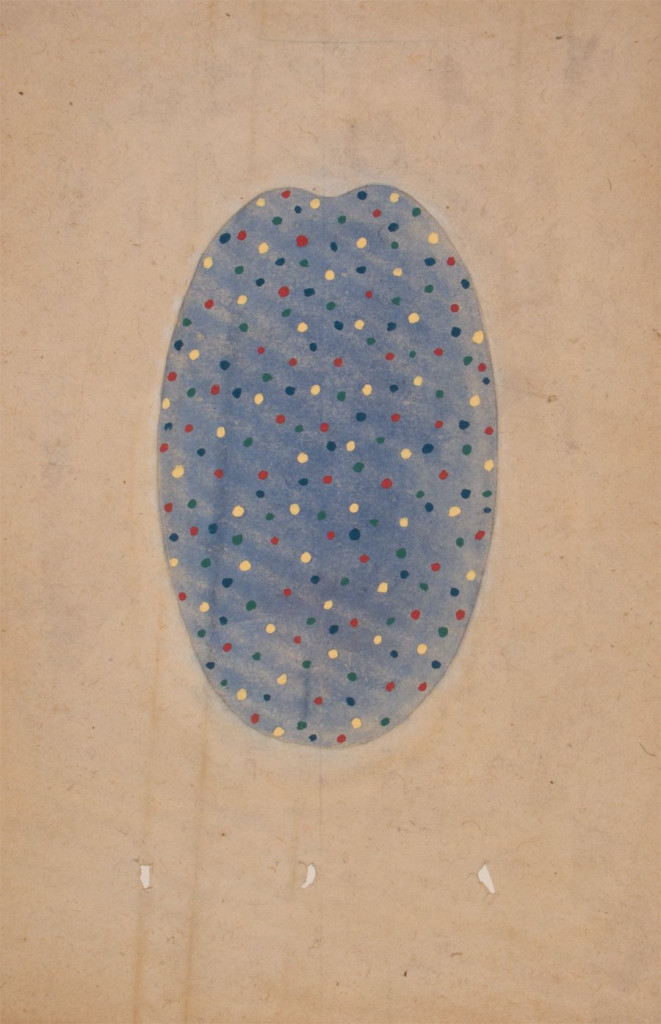

Some time ago, I can’t remember how, I came across a reference to this book. The images intrigued me, since they seemed to have so much in common with 20th century abstraction, despite their origins in 17th century Rajasthan as aids to meditation.

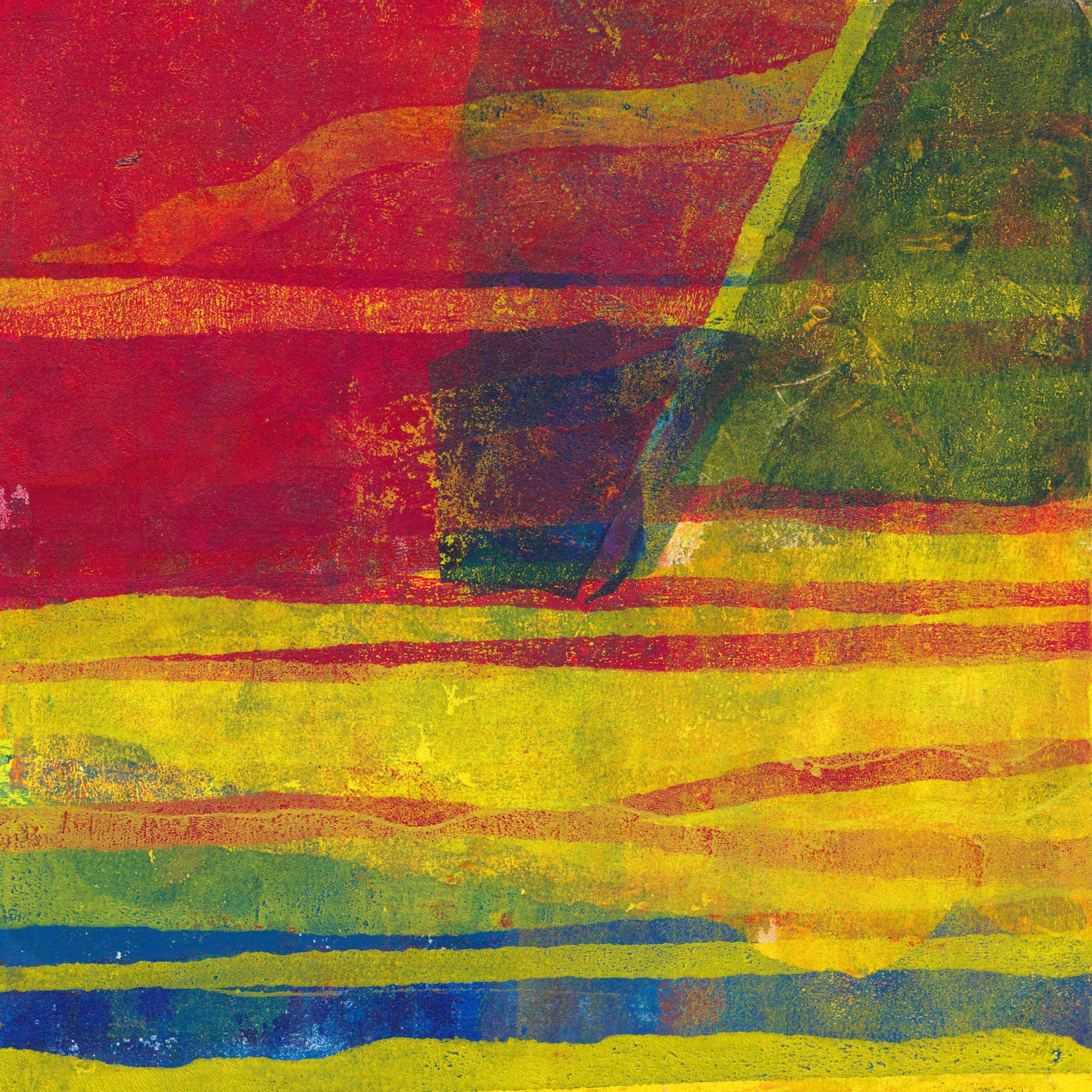

Paradoxically, the strongest visual affinity seemed to be with minimalism. Compare, for example, ‘Tremolo’ by Agnes Martin from 1962 (on the left) with this piece from the book.

The paradox stems from the symbolism of the Tantric paintings when compared with the aim of the minimalists to remove the self. To quote another minimalist, Sol de Witt, ‘what you see is what you see.’

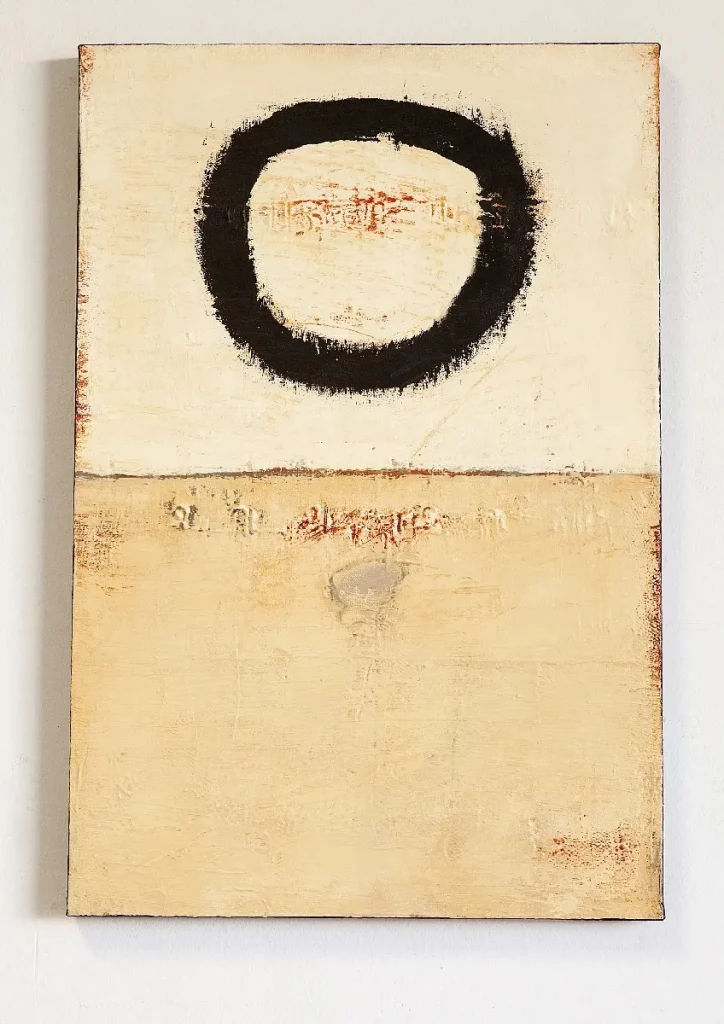

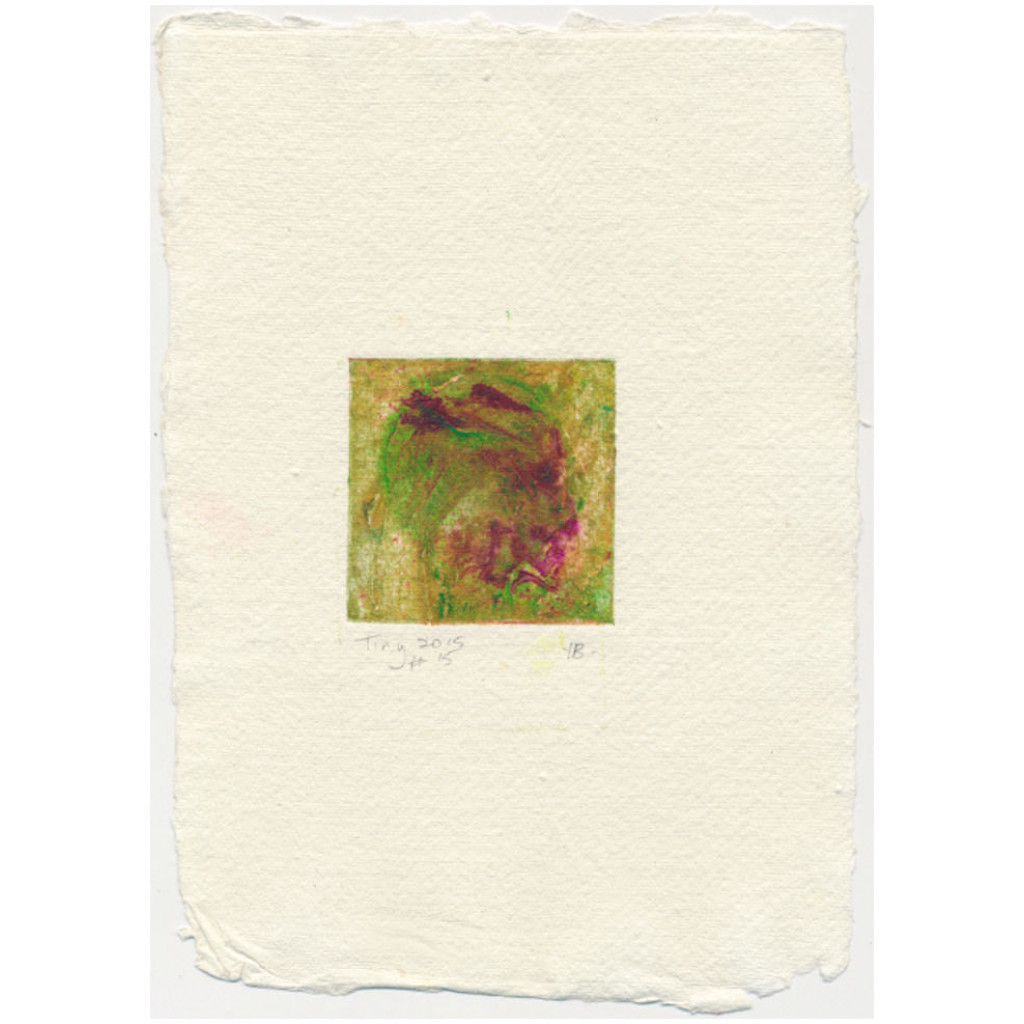

Mark Rothko, not a minimalist, described the myths of antiquity as “the eternal symbols upon which we must fall back to express basic psychological ideas.” This ties in very strongly with the work of an avowedly spiritual artist, Bill Moore. That isn’t surprising since he was an ordained Roman Catholic Priest.

“I often use cruciform shapes,” he says. “But, like Antoni Tàpies, I believe that the power of the cross goes far beyond its use in a Christian context. We’re drawn to what I call essential shapes, patterns and textures. They’re found in all kinds of civilizations and traditions. In fact, the geometric ratios that I use almost subconsciously are the same as those used in ancient Indian, Egyptian and Greek architecture, as well as medieval European cathedrals.”

https://frbillmoore.com/

The Tantric images seem to be made on similar terms. The symbols used have meaning for the devotees, although according to Jamme, these are not fixed. The images are the prop for meditation, beginning with whatever the image ‘means’. This expands and shifts as the mind explores itself.

This seems similar to the use of the Stations of the Cross in Christianity. While the images at each station can be quite elaborate, they can be reduced simply to a Roman numeral. It is the meditation on the meaning of each station that matters.

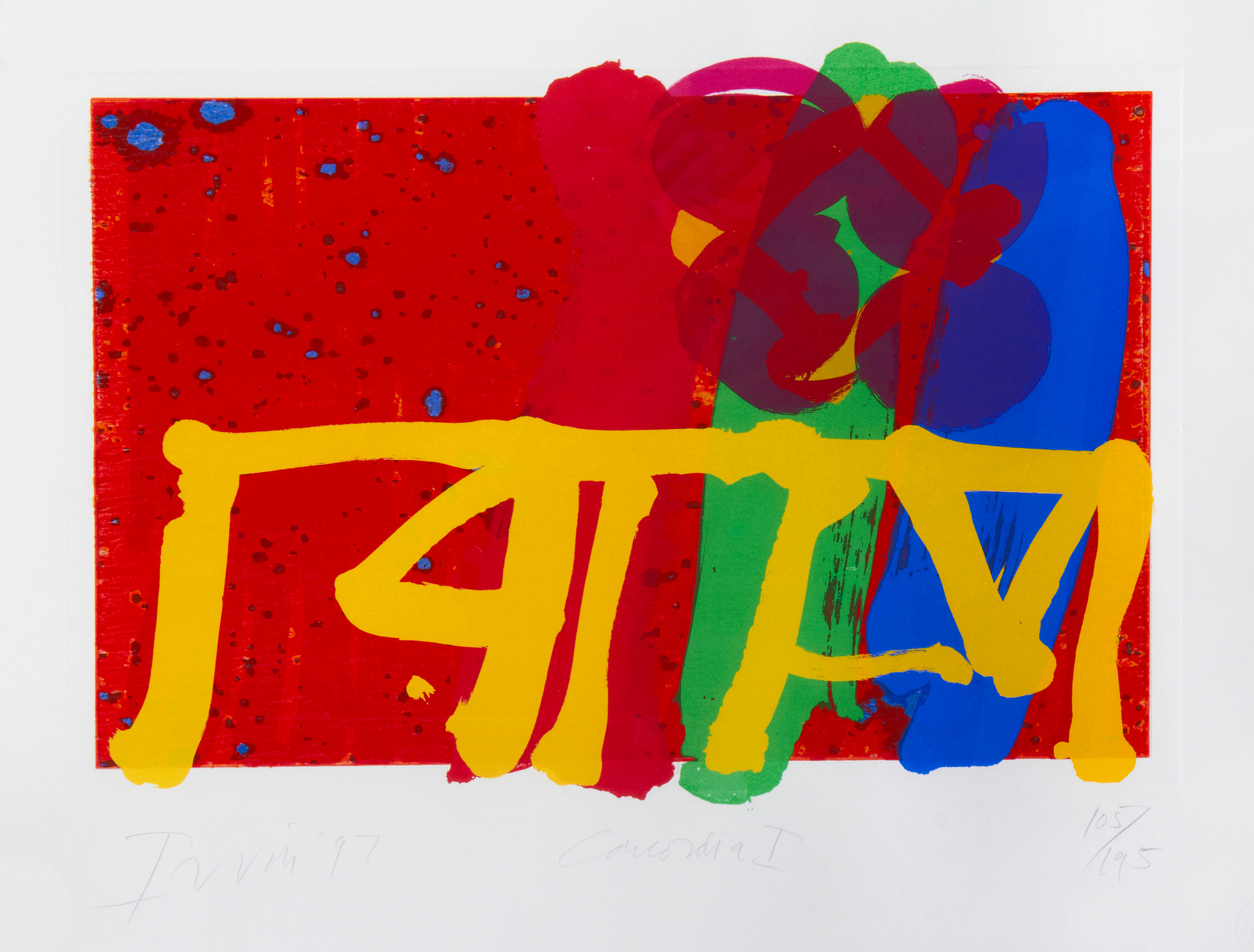

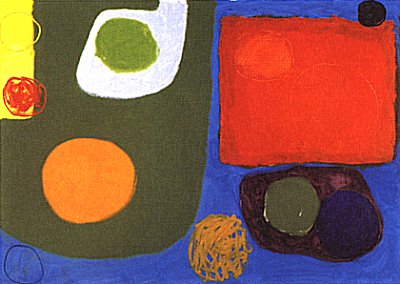

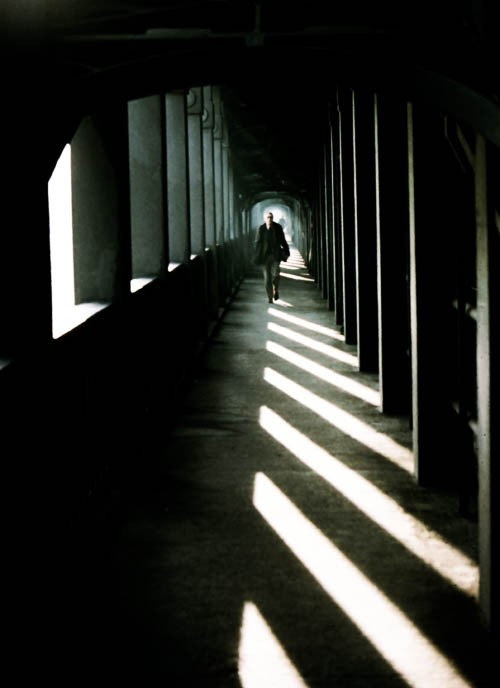

Another painter, Sir Terry Frost, (here) said: “To look at a painting which gives you the opportunity to have solitude, to be yourself and to be able to wander into reverie, is more than hedonistic, it’s spiritual”.

Until I came across that quote, I had never ‘got’ the work of Mark Rothko. I loved his way with paint, but the paintings themselves seemed shallow. Somehow it managed to pin down for me their essentially meditative nature. Which leads me back to the man himself:

“Art to me is an anecdote of the spirit, and the only means of making concrete the purpose of its varied quickness and stillness. “

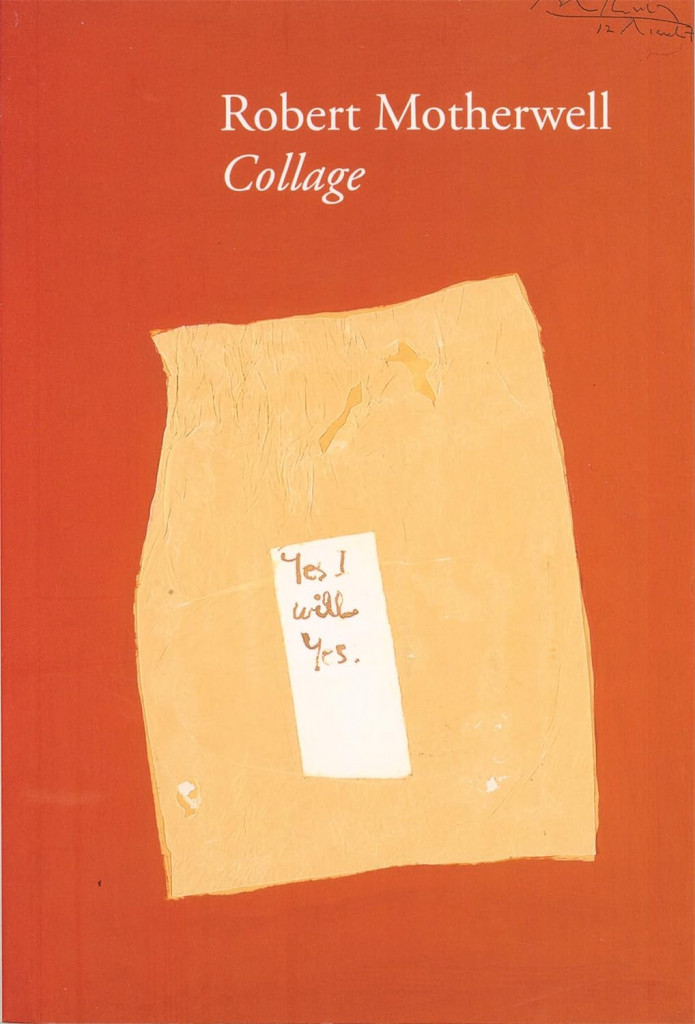

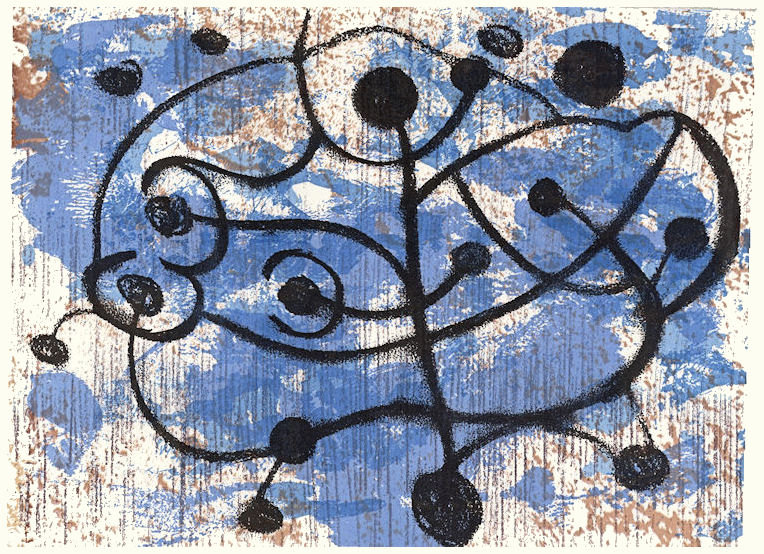

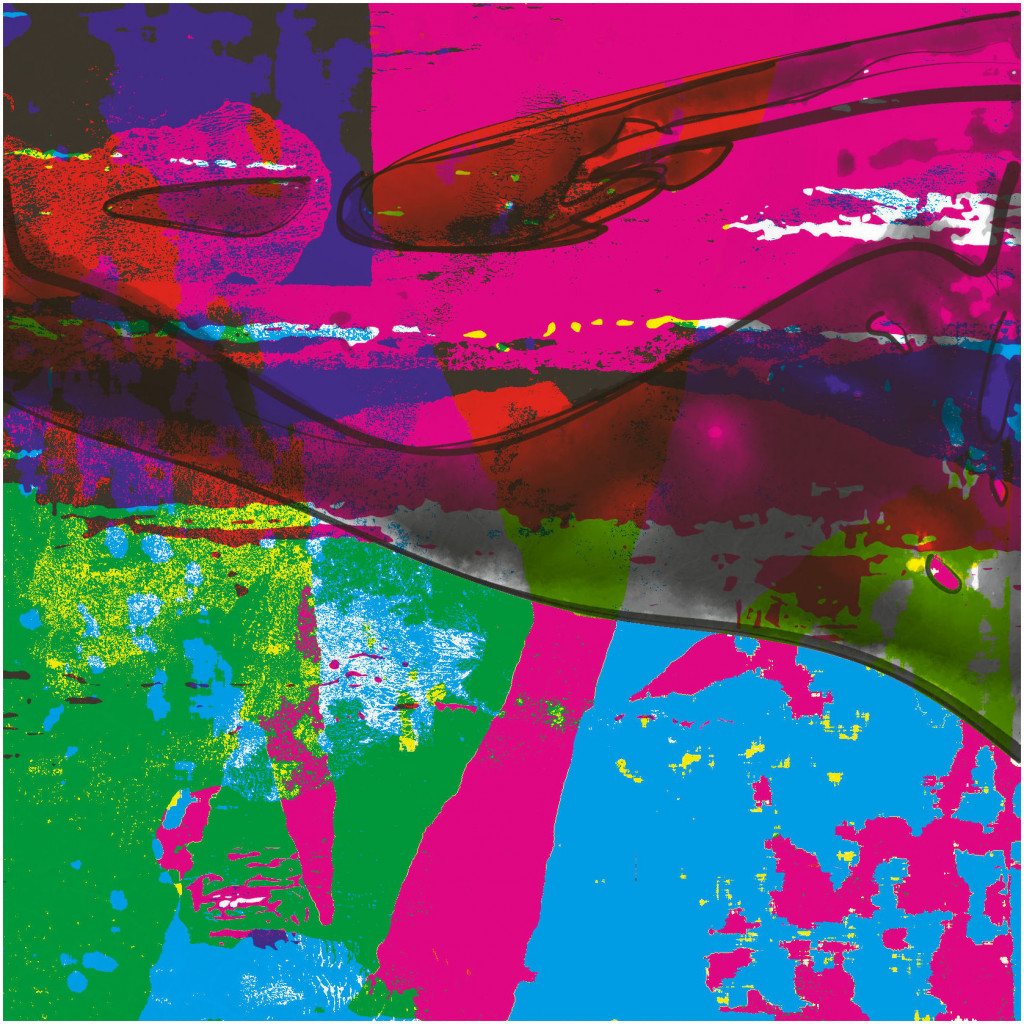

However, despite all this, the artist who first sprang to mind when I looked at the Tantra paintings, was Robert Motherwell. More specifically, it was the collage in this small catalogue from a show of his work in 2013.

(See also here)

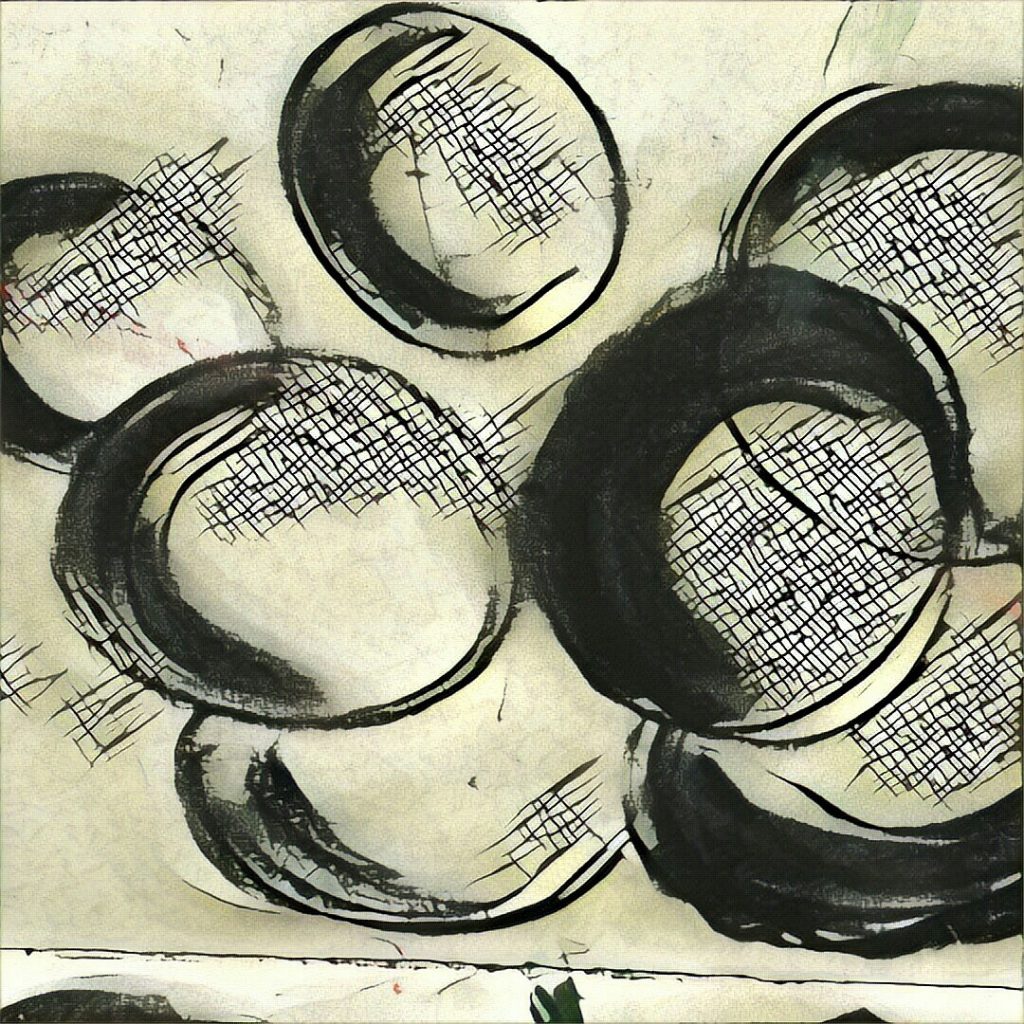

I think it was probably the simplicity of these pieces which made me draw the parallels. They transcend their commonplace, everyday origins, encouraging a similar meditative response as the Tantra paintings.

When I discovered it, the quote, from Terry Frost, gave me a focus for thinking about my own work. Until then, I think I always had, at the back of my mind, the guilty feeling that I was just making patterns. Understanding that others can find meaning in something, even if I don’t embed it there myself, liberated me. I realised that there is no meaning in abstract art. It does not require understanding. It just is. An artist may mentally attach meanings to the shapes and colours of their work, but even if they explicitly share those meanings, there can be no guarantee others will discover them or see the same things.

In the end, all art has the potential to be a subject for meditation. Even the flight of the eye across an image, is a form of meditation, a form of reverie. That is as it should be, I think. Art without emotion, seems an empty exercise.

Gallery

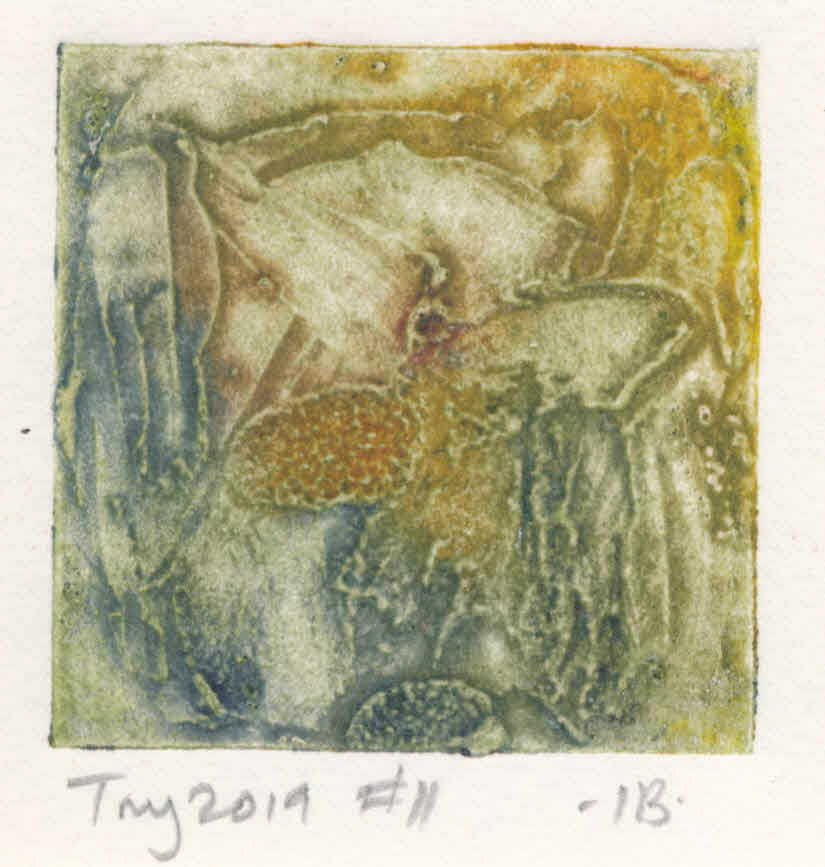

Some images from Tantra Song

Further Reading

Tantra Song

The Atlantic

The Paris Review

Hyperallergic

Robert Leeming

Bill Moore

Modernist Missionary

Stations of the Cross

My Last Art Beats (video)

Robert Motherwell

Robert Motherwell, abstraction and philosophy

Robert Motherwell, early collages

Agnes Martin

MoMA biography

Abstract Minimalism

Terry Frost

Tate Bio