Since the cave paintings at Lascaux and similar locations were painted before concepts of composition were even thought of, are they art?

Some time ago, in a Facebook group, someone asked this good question.

My initial answer was as below.

I doubt if the people making them saw them as ‘art’. That’s imposing our view of the world on the makers. From our perspective, though, yes they are art. Plus, places like Lascaux were painted by numerous hands, perhaps over centuries. They are not single compositions. What they show though is considered mark making towards an idea.

I suspect the principles they were following were more in the line of magical thinking than aesthetics. They may have thought, “if I paint this animal being killed, we will be successful on our next hunt.” Another possibility is that it was an offering to the spirit world, giving thanks for a successful hunt. Both these have been found in modern times by anthropologists. Whatever it was, they seem to have had something guiding them. They were not just throwing pigment around at random.

Sadly, the discussion didn’t progress much. The rest of this post is based on the argument I was trying to make. It includes a few extra points that didn’t occur to me at the time.

I now think the original question was based on a false premise. We don’t know if they had ideas about composition. We do know that they are not random daubs on a wall. They represent a significant human achievement, only possible because of a great deal of effort and time. They meant something to their makers.

We can never know the motives of the makers or the guiding principles they were working under. We can only speculate. Our speculations cannot fail to be coloured by our own world view, as was the original questioner.

The question of what was in the minds of the original makers of these paintings is a different question to whether they are ‘art.’ We don’t even know if the makers had a concept of art as an endeavour in its own right. There seems to have been an urge to decorate, shown in other finds from many similar cultures, but we still don’t know why it was done.

If we shift our viewpoint from looking at cave paintings to looking at scientific illustrations, it is perhaps clearer. Hooke made incredibly detailed and brilliantly executed drawings of what he saw in his microscope. These are hugely valuable in terms of their scientific intent. To see them as art means looking at them from the perspective of a separate set of values to those of the original maker. The one doesn’t negate the other. Both reference frameworks can apply simultaneously.

In the end, I suspect defining art is like defining a game. After all, what links tennis, golf, poker and Resident Evil? All games, but we would find it hard to describe the common characteristic. So in my view art includes Lascaux cave paintings, Neolithic rock carving, Medieval illuminated manuscripts, Rembrandt, Monet, Malevich, Hockney, Basquiat, and David Bailey.

Hooke is close enough in time for us to have some idea of his thought processes. I think we can feel reasonably confident that he had a sense of his work as having an aesthetic value beyond being a ‘just’ a scientific illustration. We can’t know whether the creators of cave paintings had ideas or concepts of composition, or what they were thinking. We can be sure, though, that they were thinking…

This post is related to several others about meaning in art.

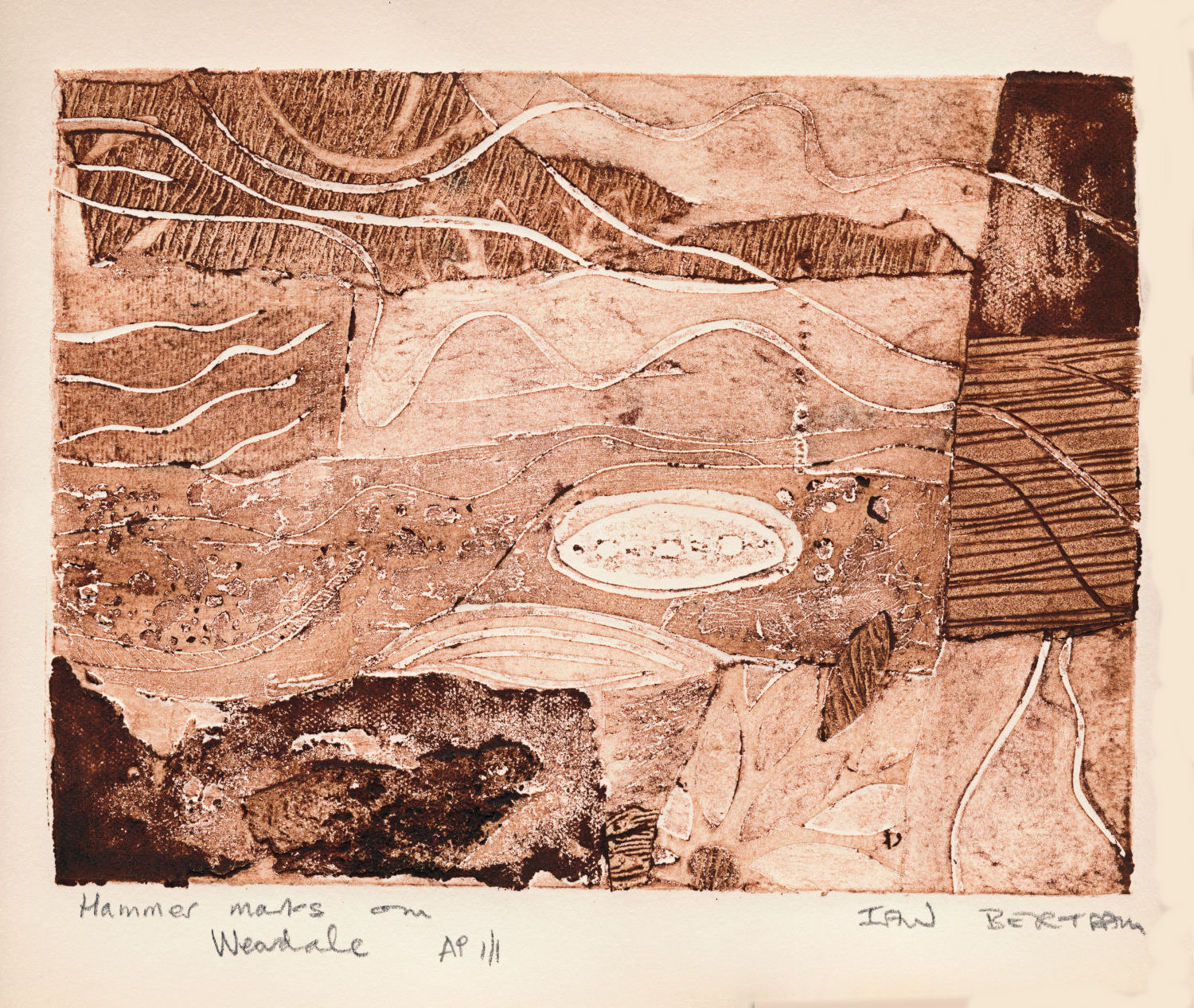

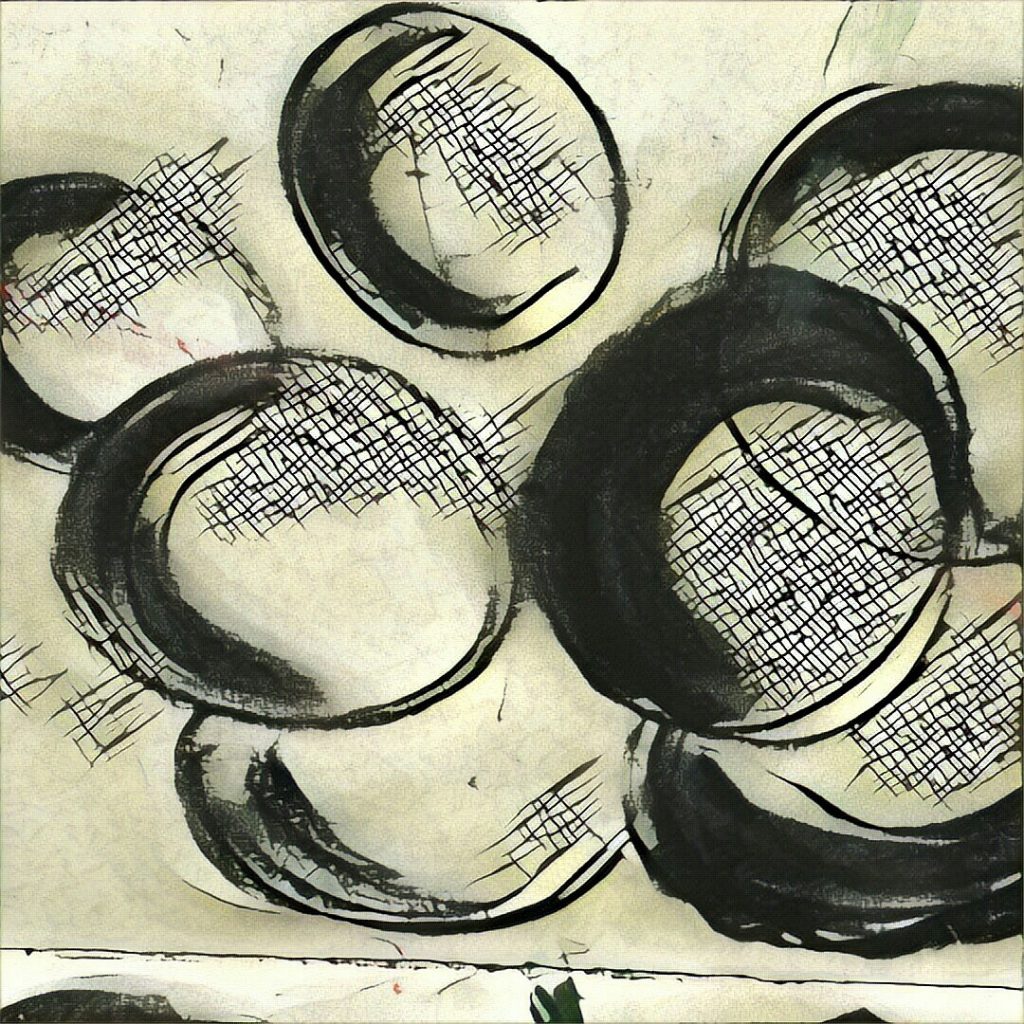

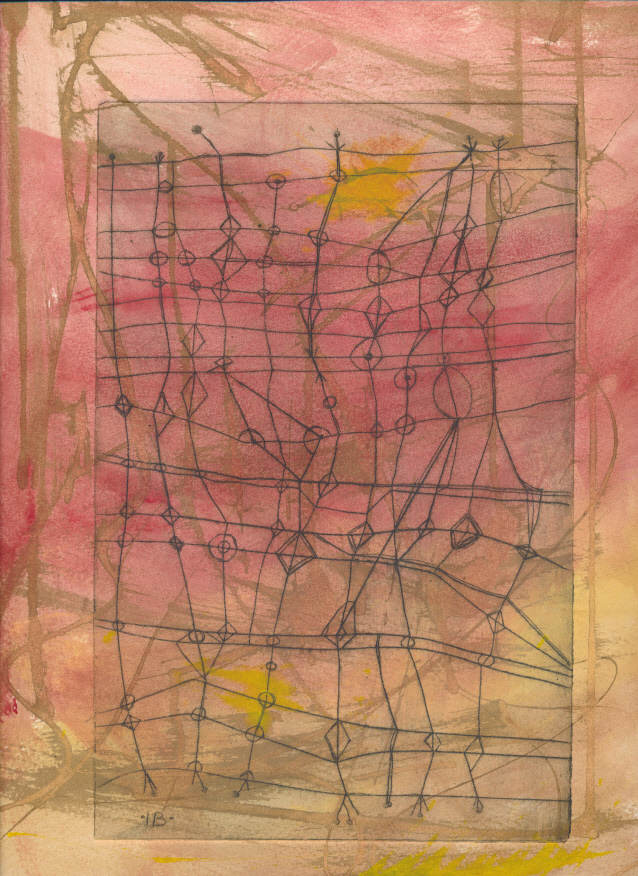

Neolithic art has also provided inspiration for many of my own prints.