Stone circles, hill figures and rock art generally have fascinated me for years. That’s why I was so drawn to the drone photographs of these artefacts, taken by David Abram, when they began to appear on Instagram. I’ve just received my copy of his Aerial Atlas of Ancient Britain. It doesn’t disappoint. The photography is stunning.

Each picture is stitched together from multiple drone photos into a single high resolution image. The image below, drawn from his website, is a good example. It shows White Sheet Hill, part of the Stourhead estate, in southern Wiltshire. On the hill there is a neolithic causeway camp and barrows, an Iron Age hill fort, and it is traversed by a Roman road.

Without these photographs, the only way to see the full extent of these ancient places is via maps and plans. The simplification inherent in their production creates a strong graphic image, which I find appealing. On the ground, they don’t reveal themselves in the same way. The attraction of the images, for me anyway, comes from the way they put these bold, graphic shapes back in their landscape settings, with all the rich and subtle colours that implies. In addition, many of these are in remote places, inaccessible to a 76-year-old with mobility problems, so they offer a vicarious experience to complement the data in reference books.

I’ve used references to neolithic art in my own work many times, and I think the Aerial Atlas will be a source of inspiration for some time.

Examples in my work

These tiny collagraphs draw on the idea of stone circles, for example.

These draw on hill figures. These are proof prints from a project derailed by the COVID pandemic.

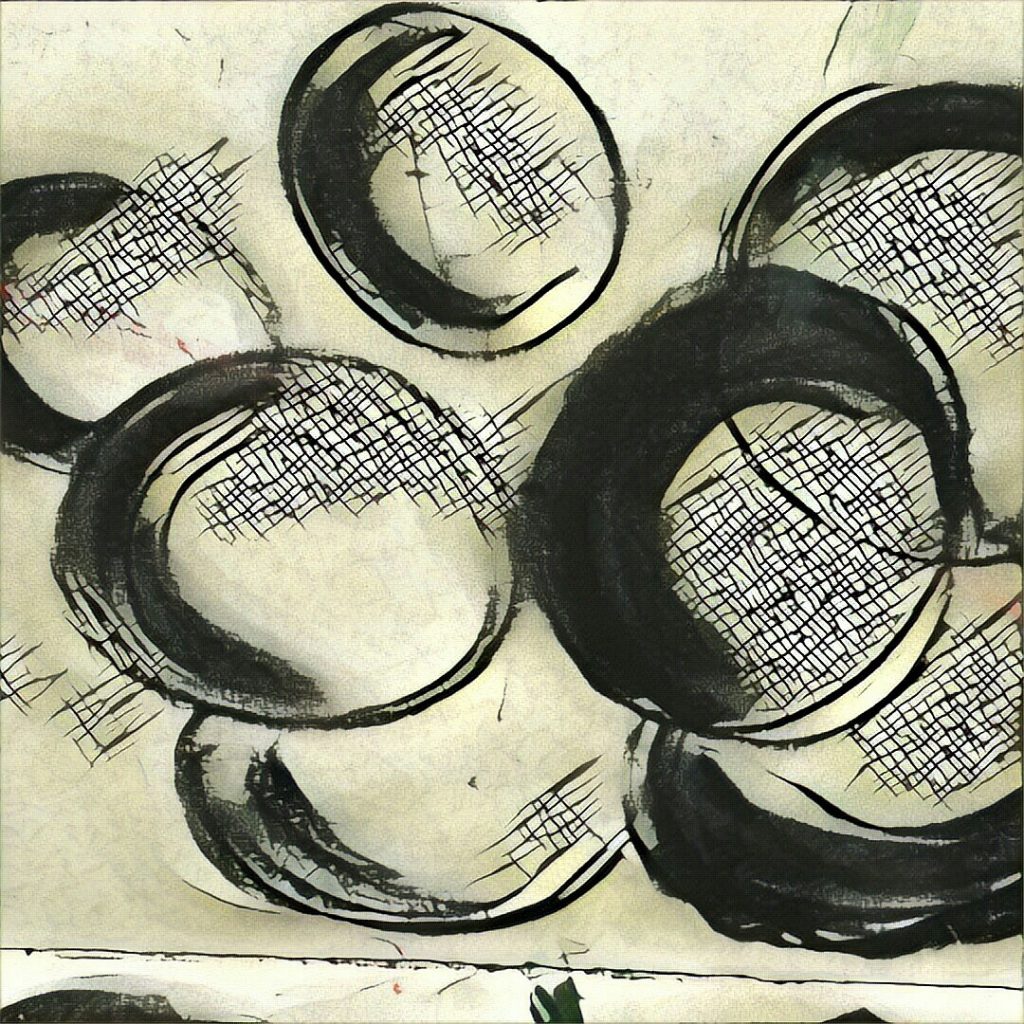

This sketch, manipulated digitally, is based on craters, but contains the same archetypal round shapes.

I have a theory, which began with art, but applies equally well to the constructions in the Aerial Atlas, that there are certain archetypal shapes with which we have a physiological as much as an aesthetic response. The obvious ones are of course line and circle/disc, but also spirals and labyrinths and probably others. The job of the artist is to tap into that physiological response. David Abram’s photos do that, I think. They expose the ‘complex simplicity’ of the shapes our ancestors created on the land, never seeing those shapes themselves, but somehow reacting to them.